Oral Histories

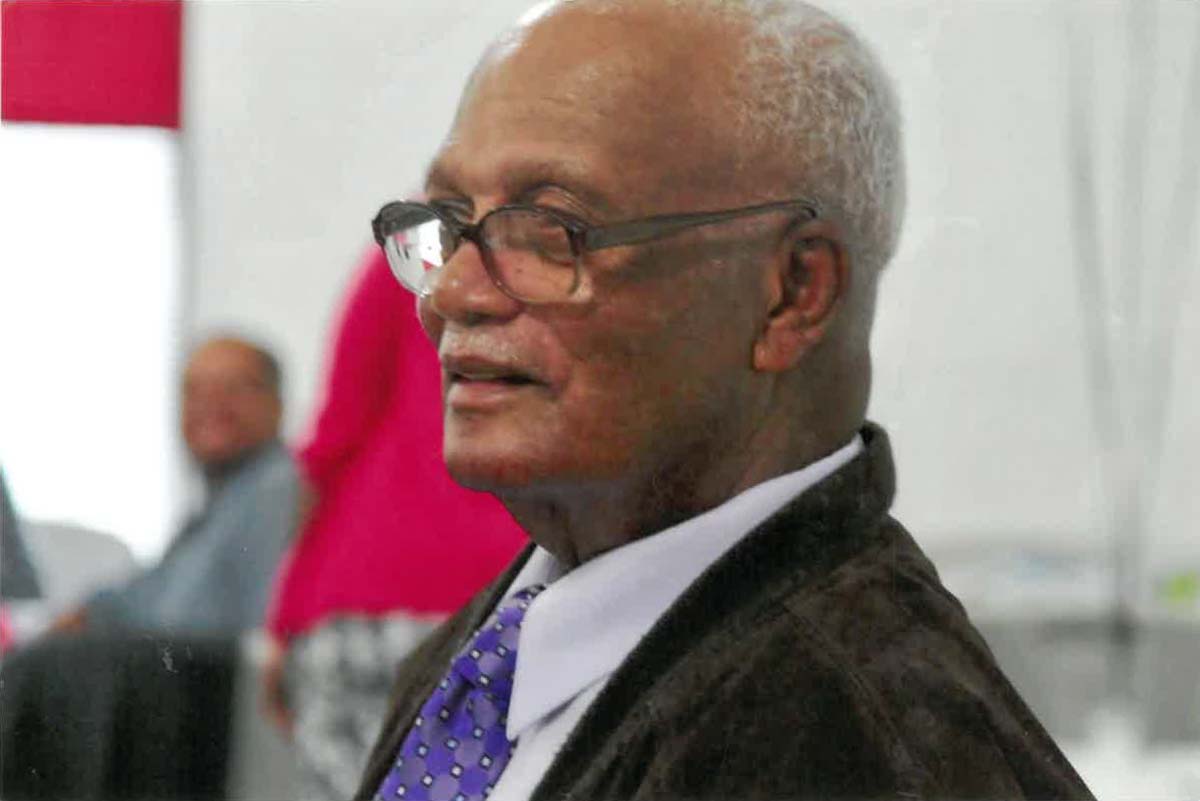

A True Ralph Bunche Trailblazer

As a child, Charles Stanley Parker knew the difference between what was unfair treatment for himself and siblings and what the white kids received. They had separate schools with modern accommodations, better treatment, accredited teachers, better tools for education and school buses to ride while they all walked to school. This was “very frustrating and there was nothing you could do about it.”

As an adult, he wanted to try to make a difference for his children. To get the ball rolling, he joined the PTA and worked with community leaders. He tried to enroll his two sons (Charles Jr. and Sherman) in the all-white King George High School, but only Sherman was accepted. While he hoped the doors could be opened for new adventures for his son, he also knew the perils every time the phone rang at work—as his heart raced and he wondered if it was about his son, Sherman.

Let Stanley Parker tell you the full story…

A Note For Readers

The Ralph Bunche Alumni Association has spent time and energy to research and archive these resources for you. We hope you enjoy what you see here and throughout this website. Please spread the word about our Association and encourage others to join. We appreciate your continuing support!

Listen to the Interview

Stanley Parker was interviewed on February 5, 2015 by Kara Saffos, a student at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia. The interview was conducted as part of the Road to School Desegregation in King George County, Virginia project.

Interview Transcript

If you would like to read along as you listen, the full transcript of Stanley Parker’s interview is included below.

Interviewed by: Kara Saffos

Interview Date: February 5, 2015

Kara Saffos: This is February 5th, 2015. This is Kara Saffos interviewing Mr. Stanley Parker. [Release forms have been signed by Stanley Parker.] Alright, to start out the interview, do you to remember what King George was like when you were a child? Can you share some of your memories about growing up here?

Stanley Parker: I don’t remember much about the school (sigh) it was so far back. We had to walk to school.

Saffos: And how far was that from here? You said you walked from here to Edgehill? And that’s on which road?

Parker: It’s on 301 now.

Saffos: 301? So that’s a pretty far walk.

Parker: Long ways.

Saffos: Do you remember any of the people that you were around during your childhood? Your friends or family members?

Parker: Well, some older people from down the road would come by walking to school and I fit in and walked with them to school.

Saffos: Oh, OK.

Saffos: Do you remember having a positive experience at school, did you like going to school?

Parker: I had no choice.

Saffos: So, your parents encouraged you to go to school?

Parker: Right. No choice.

Saffos: OK. Do you remember what your parents did for a living?

Parker: Jobbed around…wherever they could get a job.

Saffos: Do you remember some examples of what they did?

Parker: A lot of it was farming and things of that nature.

Saffos: Oh, OK. I think that’s a lot of what King George and the Northern Neck was like back then. Mostly farming communities. So, did your family live on this land?

Parker: Uh hum.

Saffos: OK. So, your parents were both from King George as well?

Parker: Yeah.

Saffos: So, your family’s been here a long time.

Parker: Yeah.

Saffos: OK. Do you remember anything about your parents’ experience in King George?

Parker: I don’t know really. I think my mother lived upstate for a while and came back here to live. Then she and my daddy got married.

Saffos: So, did your grandparents live in this area and farm or do farm jobs, too?

Parker: Yeah, they lived back down there.

Saffos: Oh OK. Do you know if there were schools available back then, for the older generations, before you?

Parker: I don’t know.

Saffos: OK. when did you first realize growing up that there was a difference between how people treated the white children and the black children?

Parker: Long ways down the road because there was never any mixing. See all these places over here, those were farms. No houses whatsoever.

Saffos: Oh, OK. So, you were kind of in your own community?

Parker: No, we were loners.

Saffos: Did you ever feel like they received better tools for an education than you did? Like with their school?

Parker: Oh, we knew they were, but we had no way to prove it. We just knew it. Yeah, because they had a bus or something to take them to school, and at the time we were walking.

Saffos: Yeah. Was that frustrating for you to see?

Parker: No, you couldn’t do anything about it, so that was it.

Saffos: OK, do you remember, I mean it’s OK if you don’t remember a lot of it. But your son was somewhat involved in the integration case, do you remember how he was involved?

Parker: Well…A fellow at our church was a minister, he lived up around DC. He drove from DC to down here to be a member of the PTA. And I was working, then I had started working at Quantico.

Saffos: Oh, you worked at Quantico?

Parker: Oh, yeah. Anything trying to make a living. Dahlgren, Quantico, worked at both of them.

Saffos: OK. So, what was your professional life like? What did you try to do to make a living?

Parker: Sometimes, I would say, it was hard. It was hard. My life was hard.

Saffos: So, you were involved in your children’s education.

Parker: I was a member of the PTA. I think that in 1948, the court had ordered them to equalize the schools, and their way of responding was to give us at least 2,000 books. So, this minister asked Matthew Bumbrey Sr and me to go to the office Fredericksburg to pick them up. Boxes, boxes, boxes of book. Brought them back to King George. They were all practically destroyed.

Saffos: Ah, OK, so you helped to deliver the infamous books, then. Oh, wow. Yeah, we’ve seen a lot of pictures, especially of the books, in the class, and that… And you saw a lot of the pages were completely torn out and a lot of them were in German.

Parker: Yeah, and I did it. So then, the minister suggested why don’t you go and apply to get your children in King George High School. And that’s when the ball started rolling. There was only two of us, Belton and me, trying to get our children enrolled from Ralph Bunche Elementary into King George High. See what happened, I filed for both my sons, and Belton for his daughter. They accepted who they wanted. They took Sherman and Belton’s daughter Margaret and rejected my older son Charles. I knew it was going to be a struggle, so I asked Sherman, did he want to go? He said yeah, he would try. So, I said, if you want to go, I’ll take you. I caught him by the hand, and walked on across to the school with him. I got to the front door. Belton’s wife, Juanita was there at the door, [they were having an assembly] and she said you can’t get in here because it’s loaded. I said okay I’ll go around and try to get in a side door. I walked around with Sherman to the side door. I walked in, and there were two ladies; the one was named Mrs. Chaplain greeted us. I told her that I had a child that I wanted to enroll in school. And, she said OK, how old is he? I told her. What grade is he? I told her [eighth] Then she said “go over there and sit down. You’ll be in my class.”

Saffos: Wow!

Parker: Right then, that day he was entered. And she said, you can go back home or to work, wherever you like, I’ll take care of him. I said I hope so. And it really broke his heart, because he was afraid you know of what was going to happen. So, then they had to have transportation for him. First Sherman had to take the bus to Ralph Bunche. Then they had a fellow that picked him up in another bus from Ralph Bunche who brought him to King George. He put him out, came back in the evening,

picked him up and took him back to Ralph Bunche. So, then he got off that bus, onto another bus to come home. That’s the way he had to travel.

The school could have been named something else but T. Benton Gayle got so mad and so evil… He named it what he wanted to name it. Gayle was something else. I never thought there would be a person like that.

Saffos: We’ve read a lot about Gayle in class and some of the things he did. Yeah, we actually were talking about it in class the other day, how the School Board was ready to move forward with integration, and even then, he was still trying to fight it.

Parker: Fight it, yeah. So that was the story. And we worried, and wondered, and worried about Sherman quite a bit. But some way, somehow, the Lord blessed him to get through it.

Saffos: Do you think that teacher that took him in that first day, helped him out quite a bit?

Parker: I think she did. I never heard from her anymore. I think she was one that was passing through. Filling in, or something like that.

Saffos: So, you did have a lot of worry about your son going to the school?

Parker: Yeah, I worried about him. Certainly, worried about him. And Sherman never told us anything but bits and parts.

Saffos: He didn’t want to worry you?

Parker: No, and he just was laid back, but we worried and we went on to work. I tell you. Girl, I was working at Dahlgren at that time. And I had two phone calls. One would be, I had no idea, but whenever it came, I said Lord, I wondered if something happened to Sherman. Was he was calling me, for something, to tell me something? Every evening I would come home, the first thing I would ask Sherman was, what was your day like, how did you get along? And he’d tell me… some things. Some things he wouldn’t. Well, it was very brave of him to continue like that. So, that went on and on and on and on.

Saffos: And your other son stayed at Ralph Bunche?

Parker: Until the next year. That’s when they opened the door for whoever wanted to come.

Saffos: Do you remember some of the things Gayle was involved in?

Parker: Gayle, I guess I just heard about him, that’s all I know. I knew where he lived, that’s all. I think I knew him when I saw him, but… he wasn’t doing anything for anyone but himself.

Saffos: Can you tell me more about your professional life? Your jobs and your time at Dahlgren and Quantico?

Parker: Well, I worked at the water plant, purifying water. And that was a struggle. Due to bad roads I used to walk quite a distance. You could take your car only so far due to so much heavy, fist sized gravel. I asked a man about putting some smaller gravel on the road. You have to buy better tires is what he told me. I came home, parked the car and the next morning I had a flat tire.

Saffos: So, you faced discrimination working there?

Parker: Yeah. So, I fixed the tire, then I had to fix how to get to work without, you know, destroying my tire. And such things as crazy two-lane highway driving and trying not to fall asleep. I can’t remember how many years I worked at the water plant but I always kept an eye open to finally get a job at Dahlgren. It was a good place to work and only eight miles from home.

Saffos: What was the last job you had at Dahlgren? Do you remember?

Parker: I was working in the tool room; repairing and issuing tools was the last one.

Saffos: I’ve heard that, you’ve been involved in the church community too. Are you a deacon?

Parker: Oh yes and both my boys belonged to the same church I did until they went off to school to furthered their education.

Saffos: Is the church community strong here in King George?

Parker: No. Honey, too many churches for the few people that go. Too many.

Saffos: Did it used to be different, when you were a child?

Parker: Oh, my God, yeah. It used to be different. You would go to church and the church would be half full of people, all the time. On the fourth Sunday which was communion Sunday, the church was two-thirds to being full. Older people have died and younger people watch the television; they don’t come to church.

Saffos: Can you tell me some more about the kind of discrimination that went on in King George or when you noticed it or when it was more apparent?

Parker: No one told me about discrimination. People just did a lot of talking was all. Lot of talking… Lot of talking… Talking was the worst thing… Worst thing.

Saffos: You said the talking was the worst thing?

Parker: You know different things, you know. Wondering different things, wondering what’s happening, what’s going to happen. Just like poor Sherman, you worried about him.

Saffos: Yeah

Parker: What was happening to him.

Saffos: But he made it through OK.

Parker: Right, that was the point! And he’s not gone. You have to ask him. Ask him what happened and what didn’t? He knows, I don’t.

Saffos: Yeah, my professor will be talking to him and interviewing him.

Saffos: So, this was actually a pretty good place to live?

Parker: Wasn’t bad, wasn’t the best. I don’t guess, but it wasn’t too bad. Just be careful where you went, who you met, who you talked to, things of that nature. And you didn’t do a whole lot of associating with people.

Saffos: Kind of had to keep to yourself?

Parker: Stayed to yourself! Yeah, that’s all you could do. My wife Violet and her parents were from Westmoreland.

Saffos: That’s where my family’s from.

Parker: Hm.

Saffos: Do you know if there were any black schools in Westmoreland?

Parker: Yeah, I know there were some down there, but I don’t know what the education situation was, but I know there were some down there. Always, even Dahlgren, everywhere there were some schools. King George was the only white school until Sherman went; that was the first time it mixed.

Saffos: So, he was the only black child in the school for a while?

Parker: The first; maybe one more.

Saffos: Oh, wow, yeah, that must have been a pretty scary experience.

Parker: Yeah, he was scared. Sometimes you begin to wonder about the kind of backbone he had.

Saffos: So, do you think that your son really opened up some doors for other people by going and showing them?

Parker: By going up there, he was I would say… “The Icebreaker”. He helped others want to go and feel that… if he can do it, I can do it. I can do the same.

Saffos: Well, that’s good, so people saw that he was able to do it. And he went on to go to college?

Parker: Oh, yeah, both of my sons. Yeah, that was my trouble, I was struggling to get both of them through college. And I did get them through college somehow!

Saffos: That’s pretty amazing! So, do you think, were you less afraid of them going to college than high school?

Parker: When they were in high school, I was afraid, but college was more of a mixture of some people.

Saffos: So, did your wife go to school in King George?

Parker: Yeah. She started off in Westmoreland and then came to King George.

Saffos: And what did she do, she did odd jobs too you said?

Parker: Yeah, just household situations in the community. She worked for a lot a lot of people. Anyone that had a job, wanted someone to work and knew they would give them a good day’s work, they contacted her. I carried her to a lot of places. Clear up until the time that the poor girl got sick. Then I drove her to doctors up and down the highway to Richmond, Fredericksburg… Lord Jesus… But the Lord blessed me to do it.

Saffos: Are there any other memories you have of King George from when you were younger, as a child and what the situation was like? Were people also segregated in public and restaurants and things?

Parker: Most of the places were a little bit segregated. You just had to watch and be careful where you went and who you were involved with, that’s all.

Saffos: Did you spend most of your time in King George and did you ever travel to visit Fredericksburg for fun and stuff?

Parker: Oh yeah, we would go to Fredericksburg whenever we got the chance.

Saffos: What did you used to do there, when you were younger? Did you eat out?

Parker: Not much, not much. Maybe buy something, bring it home.

Saffos: There was a lot of shopping there I’m sure. Was it a little bit different experience in Fredericksburg than it was in King George with race?

Parker: Oh, baby, King George always was a small place.

Saffos: Yeah, kind of a quiet place. OK, do you remember how you felt when the Civil Rights Movement was going on, or how it affected King George at all?

Parker: No. Like I said, it was 45-50 years ago, it’s hard to remember. No. People said a lot, talked a lot. A lot of things you just ignored, kept on going.

Saffos: So, I guess you kind of felt like King George was a bit secluded from the world, it wasn’t something you had to worry about every day, well except, you know, for the safety of your children, going to school. But this was, I guess kind of a good place to stay away from that.

Parker: Well you try to stay away from all troubles. Yeah, all troubles. No one tried to get involved.

Saffos: Would you say there are some pretty big differences to how everything is today than how it was?

Parker: I think so. People have accepted our race a little bit more. But some of them still have that hate.

Saffos: Well I think more people are realizing it’s a silly thing to care about. That’s why this is so important because Ralph Bunche and the black community in King George really isn’t documented that well, and that story needs to be told too. So, do you think maybe you would have wanted to go to an integrated school as a child?

Parker: Well, at the time it wasn’t such a thing, you didn’t know about it.

Saffos: So, I guess maybe society wasn’t really ready for it. So, growing up, did you just kind of assume things were going to be like that always?

Parker: Well, you thought it was. You thought everything was going to be the same way. You could just go to some places; go to Fredericksburg and to church.

Saffos: Well, I think we can stop the interview now. Thank you very much for your participation.

Other Resources

These pages are available to all to view. No password is required.

Oral History: Dr. Lillian Parker Wright

Oral History: Ralph and Earl Ashton

Become a Member

Join an Association that is committed to developing a landmark historic site in King George County, preserving the educational legacy of the civil rights movement in the United States and providing valuable assistance and resources to others. Your membership gives you access to organization news, a variety of communications, events and a member only portal. Join us today!

TAKE ACTION

Your contributions and involvement with the Ralph Bunche Alumni Association directly fund historic preservation, community education and the college scholarship award. Find out more about how you can get involved and make an important difference.